PRAYER PARTNERS

Read. Pray. Share.

We encourage you to READ and SHARE the posts and become part of the DWM community. Read more...

MINISTRY PARTNERS

Read. Pray. Share. Promote.

A Ministry Partner is also a Prayer Partner. A Ministry Partner desires to PROMOTE the Ministry. Read more...

ANGEL PARTNERS

Read. Pray. Share. Promote. Donate.

An Angel Partner is also a Ministry and Prayer Partner. An Angel Partner desires to DONATE towards the Ministry. Read more...

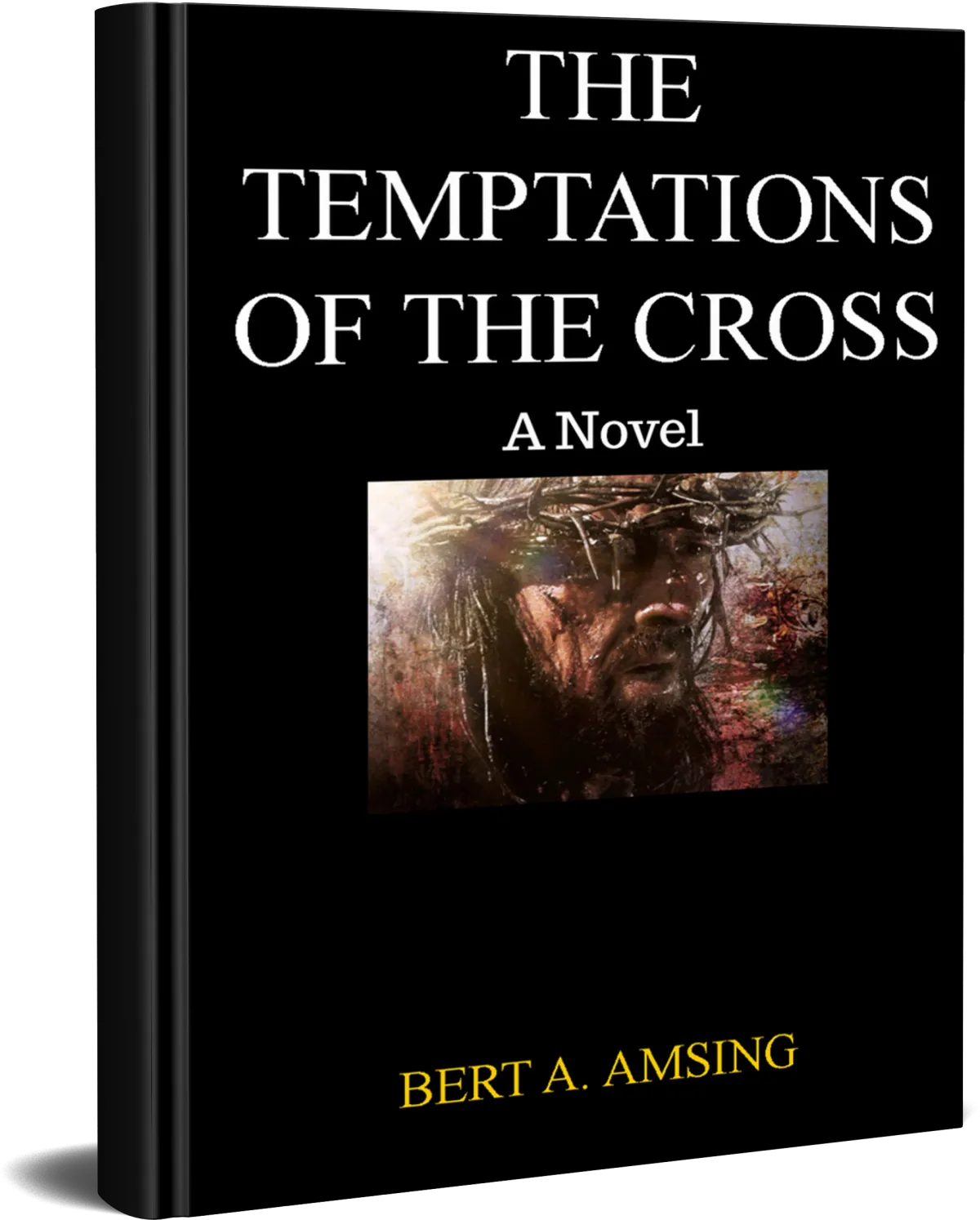

The Temptations of the Cross (A Novel)

I, Gabriel, the archangel of God, bear witness...

Lucifer unsheathed his great sword and raised it toward heaven with both hands and threw back his head to let loose a demonic scream.

"¨This soul is mine!¨"

Artwork by Astray-Engel.

All rights reserved by the artist.

Used with permission.

Click on the artwork for details

of the Creative Commons License.

Jerusalem, 66 A.D., six years before the Temple and the Holy City are destroyed by the Romans. The Jewish rebels have won a victory against the Roman legions from Syria. In the midst of the celebration only the Rabbi Gamaliel, once the teacher of the Apostle Paul, has remembered General Vespasian and his army in Egypt.

He has sent Onkelos, his most faithful student, to spy on the Romans and to put to rest the rumors of an impending invasion. The message he brings back plunges Gamaliel into a crisis that rocks the very foundation of his faith.

Gabriel, the archangel of God, takes us on a journey into the Jewish past to discover the beauty of the Days of Artistry, to feel the fear at the Sacrifice of the Promise Child, to sweat and labor in the Long Desert March.

Then we journey towards the Messianic future to join a young girl in the Birth Pangs of Promise, to suffer the agony of the Divine Irony and wonder at the Death of Sin upon a rubbish heap outside the Holy City.

It is here that we encounter the Temptations of the Cross. The temptation of Jesus to avoid the cross and the temptation of Satan to use the cross as his instrument of revenge. Upon the outcome of these two temptations hang the hopes of the nations. But Satan does not know that the Divine Sting is already in motion.

From deadly spiritual battles to quiet thoughts on the ways of God with men, from the Halls of heaven to the Gates of hell and all the drama that lies between, experience the History of Redemption like never before, as seen and told by Gabriel, the guardian angel of Jesus and the archangel of the Almighty God.

Click here to read more...

"...a powerful story, deep and rich."

Stay in Touch.

Get our Daily Readings and Monthly Newsletter.

Copyright © 2012-2023 by vanKregten Publishers and Desert Warrior Ministries.

All Rights Reserved.

Scripture is taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION.

Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984

by International Bible Society.

Used by permission of Zondervan.

All Rights Reserved.

Artwork by Astray-Engel.

All rights reserved by the artist.

Used with permission.

Click on the artwork for details

of the Creative Commons License.